Effect of nicotinamide on newly diagnosed type 1 diabetic children

Introduction

An auto-immune process involving the beta cells is responsible for the tissue damage leading to type 1 diabetes. Nicotinamide (NA), a vitamin of the B group, is one of the promising substances being considered[1–3], along with insulin, for the treatment of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus to maintain and improve their beta cell function and prolong their “honeymoon” period[1]. NA has been reported to act at 3 different levels: (1) it reduces the toxicity of free oxygen radical scavengers produced by lymphocytes and macrophages in the islet cell infiltrate; (2) it may improve insulin secretion by increasing intracellular NA-adenine dinucleotide (NAD); (3) it may promote B cell regeneration[2].

Although a number of studies have indicated that this vitamin is less effective in pre-pubertal children and more beneficial in adult type 1 diabetic patients[4,5], others have shown that the use of NA alone or in combination with vitamin E along with insulin therapy in pre-pubertal children with type 1 diabetes is able to preserve baseline C-peptide secretion for up to 2 years after diagnosis[6].

The aim of the current study was to investigate the effect of oral NA at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg per day to a maximum dose of 50 mg/day given within the first 24 h of diagnosis to children with type 1 diabetes.

Materials and methods

Children who were younger than 15 years of age and residents of Bahrain, newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and admitted to Salmaniya Medical Complex for treatment between 1998 and 2000 were eligible for inclusion in NA group of the present study. The results obtained from NA group were compared with retrospective findings from a control group admitted to the same hospital between 1995 and 1997. Only patients who were lost to follow up within the first 6 months were excluded from the study.

NA group included 66 patients who received NA in addition to sc insulin bid. The NA was given orally within the first 24 h after admission. For every 1 kg of bodyweight, a dose of 1–2 mg/day, was given but the dose did not exceed 50 mg/day. Patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic at 1 month after discharge and every 3 months thereafter for 24 months to monitor glycemic control.

Control group consisted of a 37 patients. All were admitted to the same hospital between 1995 and 1997, and were treated in a similar way as NA group, except that they did not receive NA. Control group had the same inclusion and exclu-sion criteria as NA group, and received the same management in terms of admittance protocol, patient education, discharge plan, access to endocrinologist, follow-up, insulin regime, diet, and twice-daily blood glucose testing.

On admission, the two groups were comparable in terms of age, ethnic background, sex, bodyweight, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), blood glucose and insulin requirements per kg of body weight.

A repeated measures analysis of variance, Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test, χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test (2-tailed) were performed when appropriate. The cut-off value for significance was considered to be P<0.05.

Some limitations of the present study were that we did not perform a C-peptide test (due to laboratory problems at the time of the study), and there were not equal proportions of male and female children in the study group. Some patients were lost to follow-up, and they were not traceable, which affected our HbA1c results for the 2 years of follow up. Finally, this was not a randomized control trial, but rather a trial using a historical group, which is an important limitation of this study.

Results

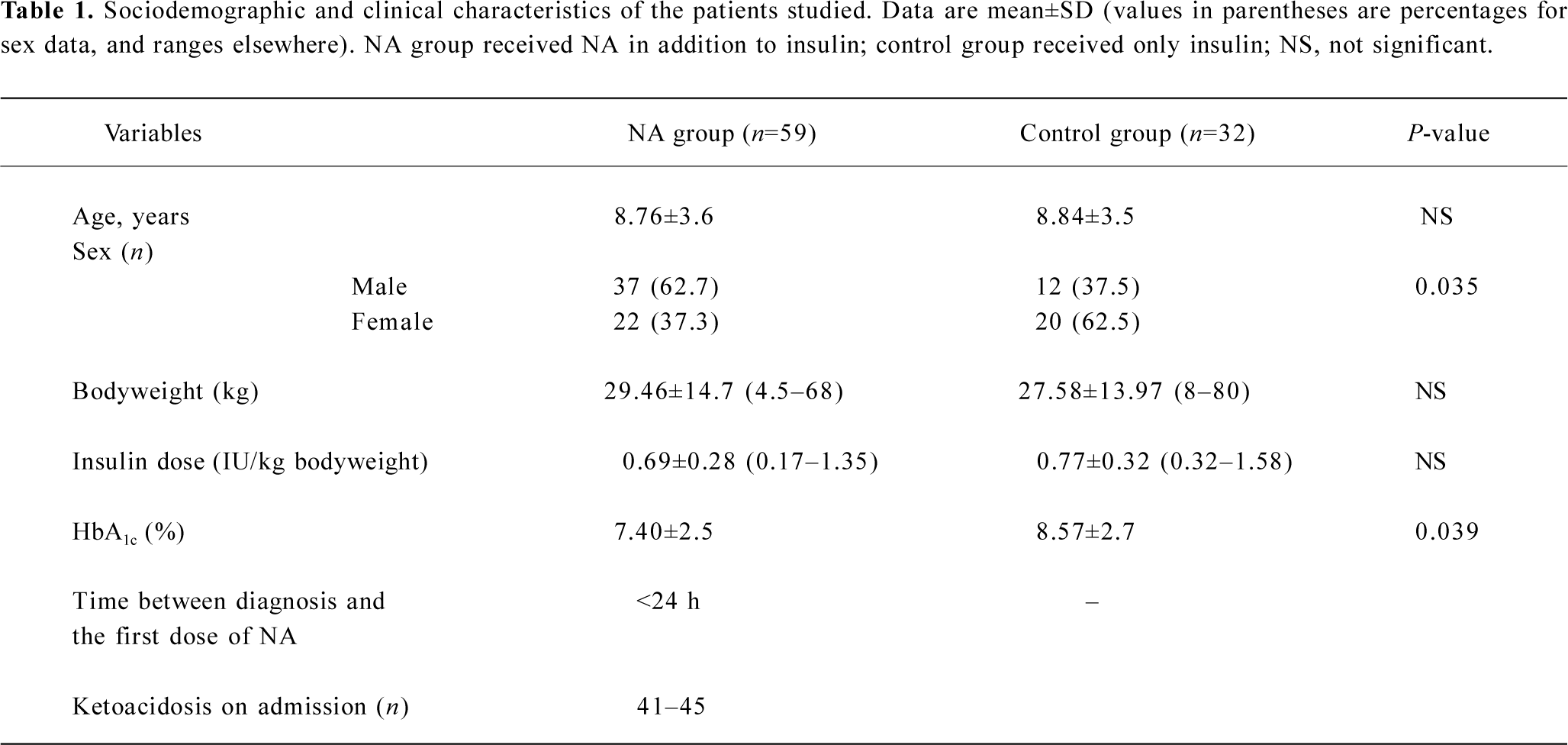

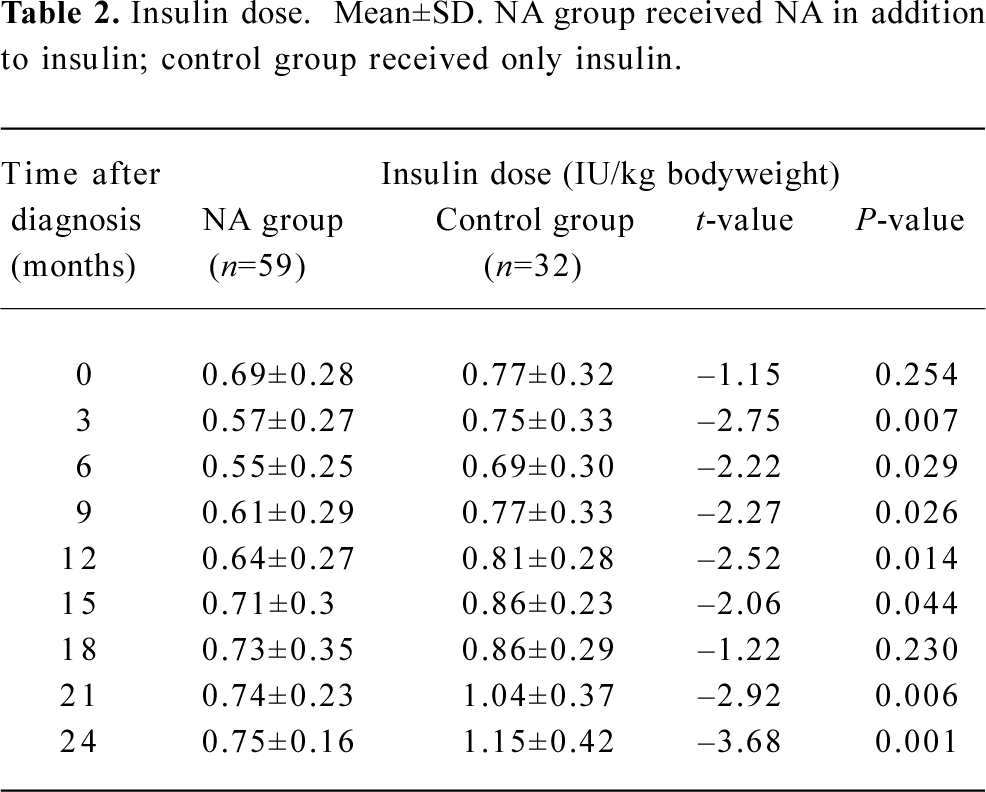

Of the patients in NA group, 7 patients were lost to follow-up, leaving a total of 59 patients for analysis. Within the 37 patients in control group, 5 were lost to follow-up, leaving a total of 32 for analysis. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of all remaining patients at entry into the trial. The insulin dose at the time of entry was comparable between the two groups (Table 2). However, the insulin requirement was significantly lower among patients in NA group at all follow-up sessions, except that at 18 months (3 months, P=0.007; 6 months, P=0.029; 9 months, P=0.026; 12 months, P=0.014; 15 months, P=0.044; 21 months, P=0.006; 24 months, P=0.001).

Full table

Full table

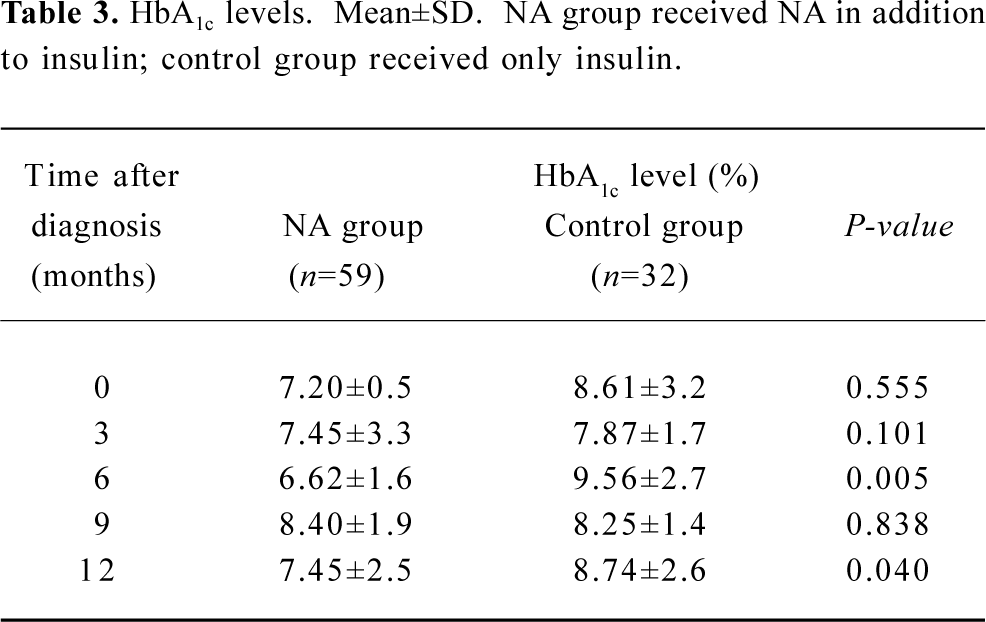

The HbA1c level at the time of entry into the study was similar between the two groups (Table 3). However, these values were significantly lower in NA group at the 6 month (P=0.005) and 12 month (P=0.0398) follow-up sessions.

Full table

Discussion

To our knowledge, apart from our research conducted in Bahrain, there have been no previous trials regarding the effect of NA on insulin requirements and glycemic control among Arab children. Our data suggest that treatment of children with type 1 diabetes with low doses of oral NA at disease onset is associated with reduced insulin requirements and improved metabolic control. This is consistent with previously reported studies, in which NA treatment was shown to protect residual B cells[1,3,6,7-12,13].

Pozzilli et al[1] noted the safety and efficacy of NA when given with insulin in the early phase of type 1 diabetes to protect and improve residual C-peptide secretion, but only in patients who are diagnosed after puberty. In the present study, patients treated with NA had better glycemic control than those who did not receive NA. Patients in NA group required a lower insulin dose per kg bodyweight for the 2 years of follow-up.

Vague et al concluded that NA slowed down the destruction of beta cells and enhanced their regeneration[9]. This is consistent with the findings of the present study. Carino et al[6] were the first to describe the use of NA alone or in combination with vitamin E, along with insulin therapy, to preserve baseline C-peptide secretion for up to 2 years after diagnosis in pre-pubertal children with type 1 diabetes[6].

Our study demonstrated the beneficial effects of low doses of NA (1–2 mg/kg) given once a day beginning within the first 24 h of diagnosis in type 1 diabetic children. Our study was limited by the fact that it was not a randomized controlled trial, but one using retrospectively gathered data.

Although we studied the effect of NA on newly diagnosed patients with type 1 diabetes, others have also studied NA as a preventive agent in individuals at risk for type 1 diabetes. Recently, the results of the European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) were published. Although no significant effect of NA in preventing type 1 diabetes was found among high-risk relatives, the conclusions of the trial were questionable due to an unacceptable drop-out rate (30%)[13].

In conclusion, our study is the first large trial among children with recent onset type 1 diabetes conducted in Bahrain or the Arabian Peninsula. Our study results suggest that even low doses of NA, when given early in the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes to pediatric patients, may prolong the “honeymoon” period and maintain residual B cell function for up to 24 months.

References

- Pozzilli P, Visalli N, Signore A, Baroni MG, Buzzetti R, Cavallo MG, et al. Double-blind trial of nicotinamide in recent-onset insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1995;38:848-52.

- Pozzilli P, Browne PD, Kolb H. Meta-analysis of nicotinamide treatment in patients with recent-onset IDDM. The Nicotinamide Trialists. Diabetes Care 1996;19:1357-63.

- Pozzilli P, Visalli N, Buzzetti R, Cavallo MG, Marietti G, Hawa M, et al. Metabolic and immune parameters at clinical onset of insulin-dependent diabetes: a population based study. Metabolism 1998;47:1205-10.

- Lampeter EF, Klinghammer A, Scherbaum WA, Heinze E, Haastert B, Giant G, et al. The Deutsche nicotinamide intervention study: an attempt to prevent type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 1998;47:980-4.

- Pozzilli P, Maclaren NK. Immunotherapy at clinical diagnosis of insulin dependent diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab 1993;4:101-5.

- Crino A, Schiaffini R, Manfrini S, Visalli N, Anguissola GB, Pitocco D, et al. A randomized trial of nicotinamide and vitamin E in children with recent onset type one diabetes (IMDIAB 1X). Eur J Endocrinol 2004;150:719-24.

- Pozzilli P, Visalli N, Cavallo MG, Signore A, Baroni MG, Buzzetti R, et al. Vitamin E and nicotinamide have similar effects in maintaining residual beta cell function in recent onset insulin-dependant diabetes (the IMDIAB 1V study). Eur J Endocrinol 1997;137:234-9.

- Kallamann B, Burkart V, Kroncke KD, Kolb-Baclofen V, Kolb H. Toxicity of chemically generated nitric oxide towards pancreatic islet cell can be prevented by nicotinamide. Life Sci 1992;51:671-8.

- Vogue P, Vialettes B, Lassman-Vague V, Vallo JJ. Nicotinamide may extend emission phase in insulin dependent diabetes. Lancet 1987;1:619-20.

- Bowman MA, Leiter EH, Atkinson MA. Prevention of diabetes in the NOD mouse: implications for therapeutic intervention in human disease. Immunol Today 1994;15:115-20.

- Pozzilli P, Visalli N, Buzzetti R, Baroni MG, Boccuni ML, Fioriti E, et al. Adjuvant therapy in recent onset type 1 diabetes at diagnosis and insulin requirement after 2 years. Diabetes Metab 1995;21:47-9.

- Vague P, Picq R, Bernal M, Lassmann-Vague V, Vialettes B. Effect of nicotinamide treatment on the residual insulin secretion in type 1 (insulin-dependant) diabetes patients. Diabetologia 1989;32:316-21.

- European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT): a randomized controlled trial of intervention before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2004;363:925-31.